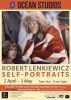

This illustrated essay is undated but it clearly a journeyman work. It's subject is the Spanish master Diego Velazquez (1599-1660), court painter to King Philip IV. Contents: 14 pages and one loose leaf, 380 x 315 mm, cartridge paper.

"Amidst Philip the Fourth’s character, totally unsuited for his position, survived one rare talent, the talent for recognizing other talent. Spain had and has little to thank him for but, of the little due to him surely his patronising of Spain’s ablest painter justifies his existence."

[Transcription from the essay.]

Amidst Philip the Fourth’s character, totally unsuited for his position, survived one rare talent, the talent for recognizing other talent. Spain had and has little to thank him for but, of the little due to him surely his patronising of Spain’s ablest painter justifies his existence,

The higher we soar the further away do we appear to those who cannot fly.

Nietzsche.

Diego Rodriguez de Silva y Velazquez, was born at Seville, in 1599 and baptised in the parish church of San Pedro on the i6th of June. The father of the artist followed the legal profession and his wife Geronima looked after the boy, 'instilling into his young mind the principles of the virtues and the milk of the fear of god'.

They likewise gave him the best scholastic education that Seville afforded, in the course of which he showed an excellent understanding and acquired a competent knowledge of languages and philosophy.

He reputedly displayed his aptitude with diligent drawings on his grammar and copy books, with the result that his father was content that the boy should be placed under the tutorship of the fiery-tempered Herrera; a clever, excessively dexterous painter whose unrestrained disposition frequently scattered in dismay the large band of disciples he had attracted.

Velazquez, being quiet and gentle in temperament, grew weary of the irascible master, and thereby resolved to move to a more peaceful and orderly school.

His new instructor, Francisco Pacheco, was in all respects the very opposite to Herrera – a busy scholar and a polished gentleman, a slow and laborious painter whose work, perhaps graceful, was always deficient in force, he was as incapable of painting Herrera’s St Hemengild as he was of thrashing his pupils.

Velazquez decided however that nature herself was the artist’s best teacher, and work his surest guide to perfection. He resolved at youth neither to paint any object nor sketch it without having the thing itself before him.

That he might have a model ever at hand ''he kept" says Pacheco, "a peasant lad as an apprentice, who served him for a study in different actions and postures – sometimes crying sometimes laughing – till he had grappled with every difficulty of expression and from him he executed an infinite variety of heads in charcoal and chalk on blue paper, by which he arrived at certainty in taking likenesses, so laying down the foundation for the cunning ease with which he later painted heads. There is a story that his excellence was admitted even by his disparagers – that he could paint a head and nothing else, to this, when repeated to him by Philip the fourth he replied – that they flattered him for he knew of nobody who could paint a head thoroughly well.

Velazquez proceeded with the study of low life found in the streets of Andalusia, to this epoch is referred his celebrated picture the "water carrier". I should like to suggest that I do not believe this painting validates it’s supposed merit, there is to be sure a remarkable technical [skill] displayed for a youth of 19, more in its draughtsmanship than in its paint application, but a skill so staggeringly inferior to his later work, that i feel a little of the light shed on this painting should be spread over other youthful works, particularly the less lauded "woman cooking eggs".

He remained constant in his apparent preference for the actual rather than the elevated and ideal, and to those who proposed a loftier flight suggesting Raphael as a nobler model than Luis Tristan the favourite scholar of El Greco, whom Velazquez frequently confessed his obligation to; – he used to reply that he would rather be the first of vulgar painters than the second of refined ones. Vulgar i suspect being indicative of the realist and refined suggestive of the idealist, a precept he rarely forsook.

After a laborious course of study Velazquez became the son in law of his master, "At the end of five years spent in what may be called an academy of good taste" says Pacheco complacently, ''he married my daughter, Dona Juana, moved thereto by her virtue, beauty, and good qualities, and his trust in his own natural genius".

Little is known of this woman beyond the fact of her marriage.

There is a profile portrait in the Prado which reputedly is his wife, if so, she appears to, lack the conventional necessities for beauty. She apparently bore him six children: four boys, two girls. Of their domestic life nothing has been recorded: there appears to be no reason to believe that Juana Pacheco proved herself in any respect unworthy of her father’s praises.

For forty years the companion of her husband through his remarkable career, said to have closed his eyes when he died, and within a few days was laid beside him in the grave.

If the artistic instructions of Pacheco were of little value to Velazquez, me must at least have benefited by his residence in a house which really was as regards its society, the best academy of taste Seville afforded.

There he conversed with all that Andalusia could boast of intellect and sensitivity. Velazquez, palomino says, studied the writings of Durer, to gain knowledge of the human frame, and for perspective he studied Porta and Barbaro. He made himself master of Euclid’s geometry, and Moya’s treatise on arithmetic, and he learned something of architecture from Vitruvius and Vignola.

At twenty three Velazquez journeyed to Madrid and after some months study at the Prado and The Escorial returned to Seville. During the next few months after his departure, Fonseca, his friend in Madrid, succeeded in interesting the court Duke Olivarez the favourite of the king, on Velazquez’ behalf; and recalled the young Sevillian to his house where he painted Fonseca's portrait, which, when finished was carried to the palace, seen and admired by the king and many grandees; thus the fortune of Velazquez was made.

Velazquez was formally made or appointed painter in ordinary to the king on the 31st of October 1623. He brought his family to Madrid and was provided with apartments in the treasury.

During the following years little occurred to prove him other than a quiet and reasonable person; no fights as with Caravaggio, no great losses as with Rembrandt, no great fame as with Rubens; but an almost silent production of some of the world’s finest painting. In 1629 he visited Venice, Rome, Genoa, Bologna, and Naples, becoming a friend of Ribera's in the latter city.

He copied renaissance paintings and in Rome painted "The Forge of Vulcan". This painting is rendered with a far greater fluidity than before. It again displays his remarkable technical competence and facility. As far as i can see his friendship with Rubens had little if no influence on his work.

On his return to Spain he painted his famous "dwarfs and buffoon". The choice of these subjects is not due to a humane character deigning to paint these so-called pitiable creatures, but surely to the fact that they had visually staggering heads and figures to paint, and they roamed the palace with one thing in common with the king; very little to do. In 1635 he painted "The Surrender of Breda" with its impressive composition. He had now abandoned all classical tendencies save a Venetian influence.

Apart from the original sensitive awareness, the creating of art, be it music, literature, sculpture, or painting, appears to me to be little short of a science; in the case of painting, the use and application of the materials, or the choice of subject, display emotion, indeed inevitably so. But all the applications on the canvas of the myriad intricacies entailed in hours of highly developed perception is surely mathematics.

I should like to suggest that in the mathematical sense Velazquez is superior to all, superior to Rembrandt and Vermeer, to Chardin and to Degas.

It has however been implied that Velazquez is lacking in humanity. Rationality replies that his intense perception can only be indicative of great feeling, and vision replies in the painting “The Surrender of Breda”; what more humane gesture than the victor laying his hand on the shoulder of the vanquished. In 1649 Velazquez again travelled to Italy, purchasing old masters to satisfy the king’s apparent appetite for paintings; on this occasion he painted his staggering portrait of pope innocent the tenth. Reynolds considered it the finest painting in Rome, and Schopenhauer said that before it one feels one is standing in front of the majesty of the earth. After his return in 1651, his official duties as superintendent of the palace cut seriously into his painting. However he had time to paint such works as the light-saturated "Tapestry Weavers", the fresh "Rokeby Venus" and – the climax of his life – "Las Meninas". The epitome of his perception, a large air-filled canvas, and one i can talk about only from reproductions. How Velazquez achieved its tranquil reality is to me unfathomable; one detects perhaps such technical tricks as the fact that the foreground figures appear more intense than the middle distant figures, and those more intense then the far distant ones; the effect of distance is heightened by the reflection of the king and queen in the far-off mirror. I have heard it said that the design and construction of this painting is almost frighteningly complicated, in fact the complete opposite to what it appears to be. I myself however am as yet unable to penetrate its mysterious architecture. I can say no more therefore, other than the fact that this piece of canvas feels permeated with life, that air has lifted the paint so to speak, as to create reality in itself.

Velazquez’ skill, the most facile any painter has possessed, does not stop at the clever manipulation of the brush; Frans Hals has been called the crack shot of the brush, for its control painters like Manet and Sargent have been respected; but if skill entails the awareness of tones and colours and shapes, the degree of perception must thereby condition the standard of the creation. There are as many perceptions as there are individuals, but each or some of these perceptions, be they intensely emotional or intensely objective, can roughly, I suspect, be formulated into groups; and within these groups can perchance be observed the standard of the artist.

There is in this statement an evident contradiction, but by using the term ‘grouped-individuals’ in its context I pray a grain of truth can be extracted.

There is one portrait, the head and shoulders of Philip the Fourth, painted in 1656, which I believe says all about Velazquez that need be said; of this amazing portrait a contemporary said “so life-like all it needed was a voice”.

References:

Velazquez-Ortega y Gasset. Printed in Switzerland by Conzett & Huber, Zurich. Collins publishers London.

Stories of the Spanish artists – Sir William Stirling-Maxwell & Luis Garreno.

Printed by BallantYne, Hanson & co. Edinburgh & London.

National gallery. Apsly House. The Wallace Collection.

Figures

Fig.1

The Surrender of Breda – “Las Lanzas”

This painting reveals many remarkable details, particularly the group of soldiers on the left. The freer technique now adopted is admirably suitable. The 28 vertical lances piercing more than a third of the landscape and sky is an unusual feature. Of Spinola’s compassionate gesture; Calderon in a play on the subject has him say: “Justino, I receive them (the keys) and I know how valiant you are and that the valour of the conquered brings fame to the conqueror.

Fig.2

This dwarf actually held an official position as assistant in the King’s chancellery, and Philip jovially called him “Primo” – that is, cousin.

Fig.3

Innumerable copies have been made of this magnificent picture, considered one of the best portraits of all time. Apparently all Rome was eager to have a copy of this Holy Father, and this may explain their great number.

Fig.4

Little, I fear, can be said about this freakishly competent portrait other than the already quoted statement regarding its reality.

Fig.5

Detail of-: The Maids of Honour. This is the only self-portrait of Velazquez known to be authentic. According to Palomino, the red cross of the Order of Santiago was added by command of the king after the death of the painter. The legend says Philip IV with the brush himself decorated his friend as a mark of favour and gratitude.

“Las Meninas” – known also as “The Maids of Honour” and as “The Family” – is regarded as the artist’s finest achievement. Reputedly, if there be such a thing, the favourite painting of both Dali and Picasso. The whole group in the foreground is apparently watching the King and Queen, the double-portrait of whom is seen in the mirror in the background. It is still undecided by the experts whether Velazquez is actually painting their portrait or whether they are looking in on a sitting of the Infanta and her ladies, – perchance a painting of both.