Works from what became Project 18, 38 in all, were first shown at the New Street Gallery between 17 December - 28 January 1989. Two further showings of work followed there in January 1990 (47 works) and between 3 September – 2 October 1990 (54 works).

The exhibition at the Birmingham ICC in January 1994 included 105 works from Project 18 and 77 works in a 'retrospective' section spanning the artist's career. (See Exhibition List).

Lenkiewicz’s diaries record that attendance figures at the Education exhibition were disappointing. What little press coverage the show received simply rehashed the previous controversies and stereotyped the artist as a vain self-portraitist or painter of racy nudes. After seventeen carefully researched Projects examining the human condition, Lenkiewicz asked himself in his diary, “Why do I bother?” A new Project called The Painter with Women: Observations on the Theme of the Double, grew out of his frustration. If he was to be pigeonholed as an egotistical or salacious painter, then he would come up with something truly “enraging”.

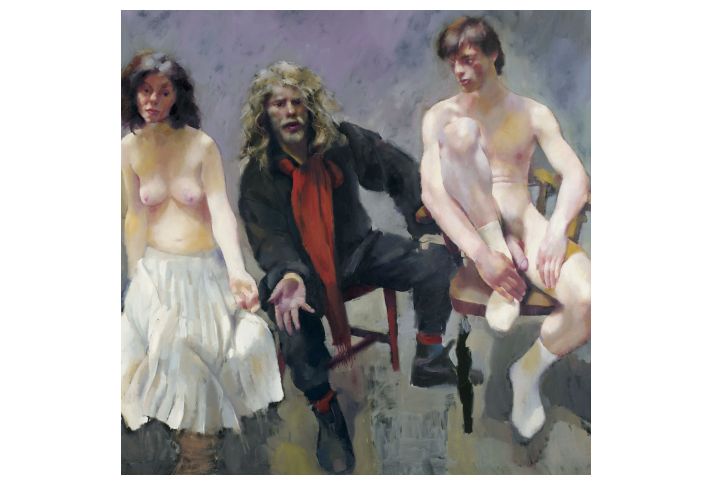

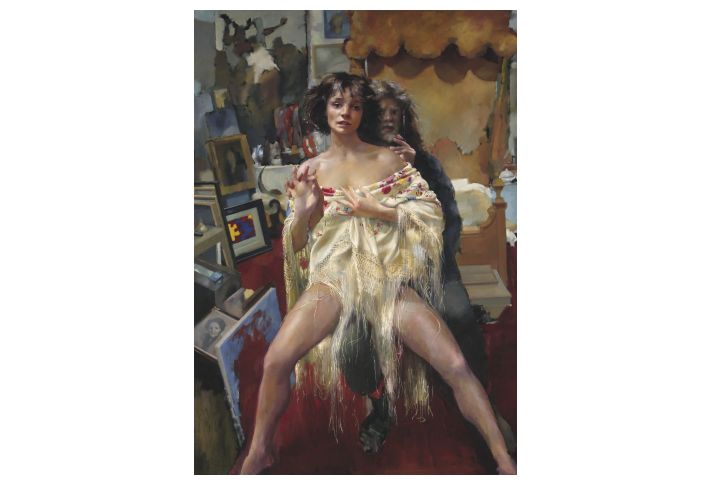

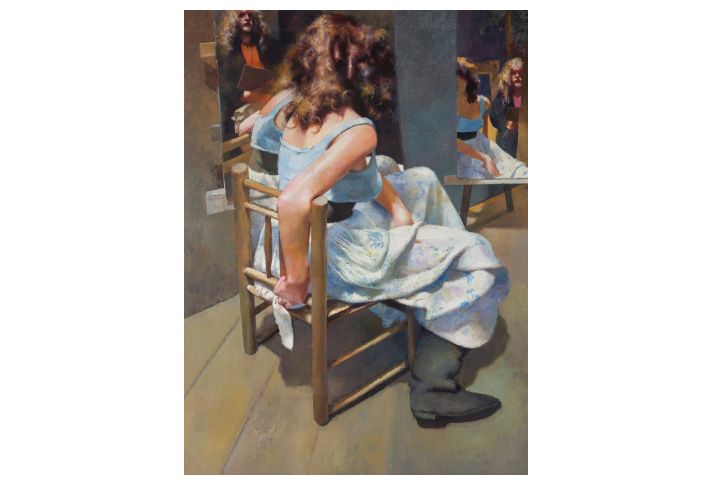

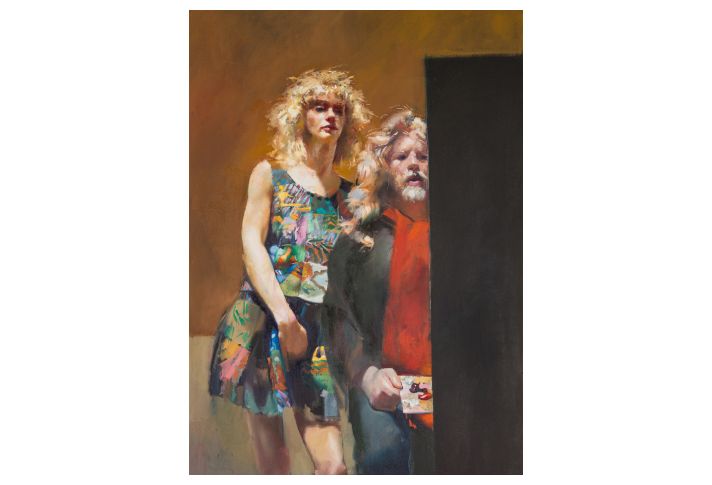

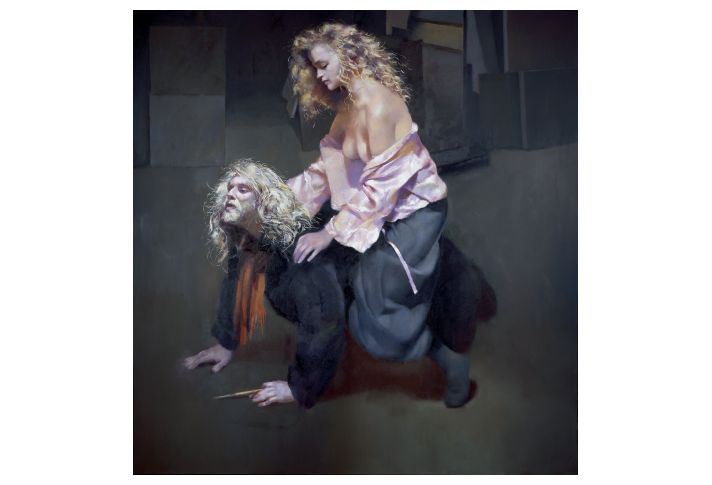

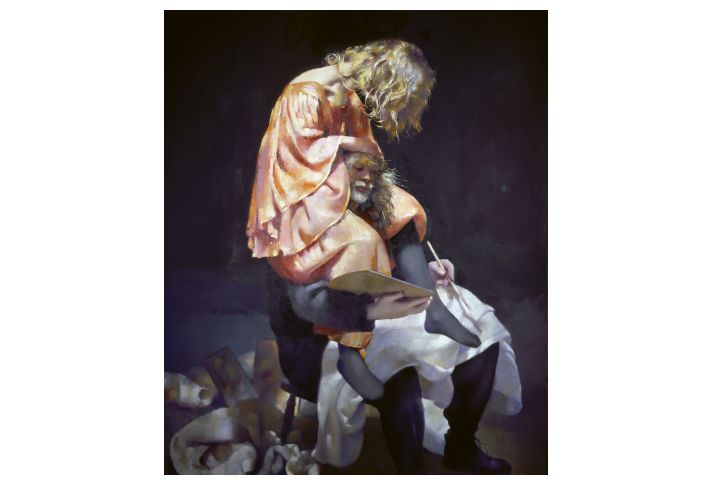

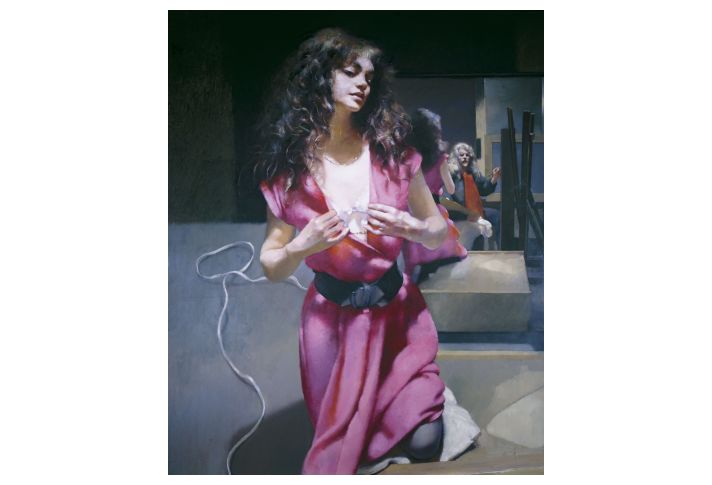

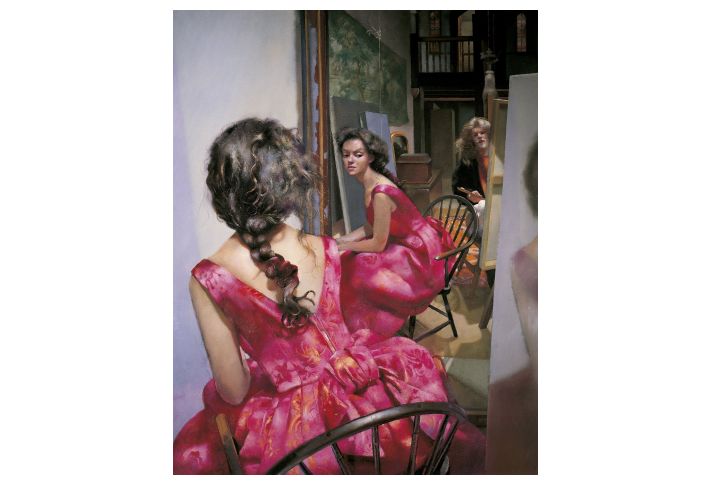

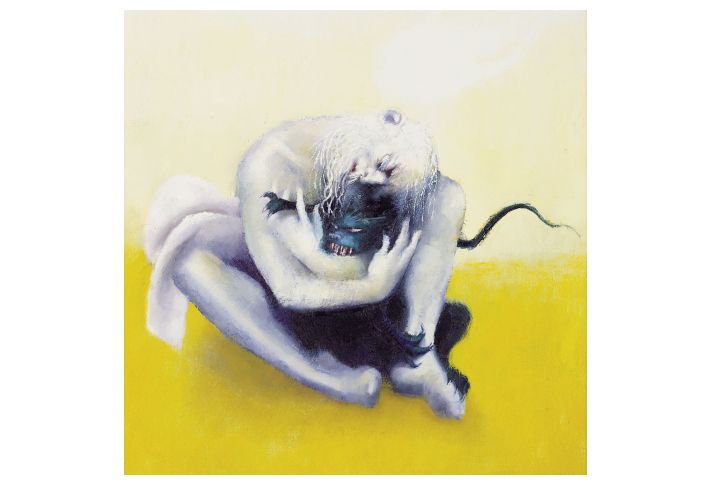

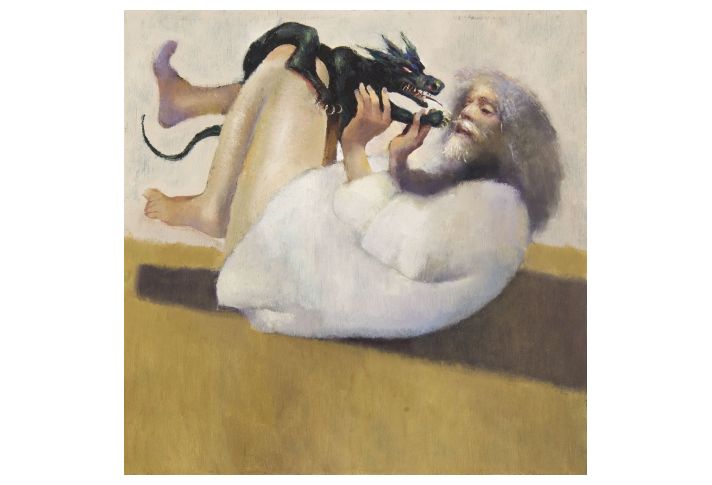

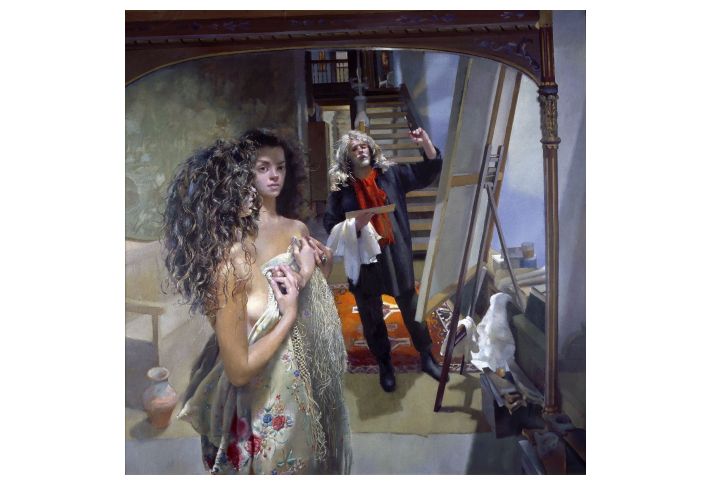

Lenkiewicz based the Project on his thesis that relationships are mirrors, that ‘the other’ merely reflects back our own aesthetic preoccupations. As the Project developed, it was divided into themes which echoed art historical treatments of the relationship between the sexes, such as Carità Romana, Aristotle & Phyllis, Samson & Delilah, and the main St Antony theme, for the ascetic hermit who overcame lustful temptations sent by demons.

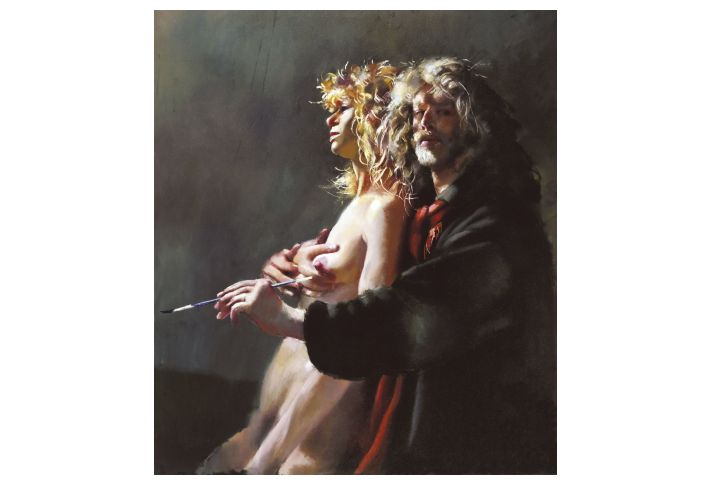

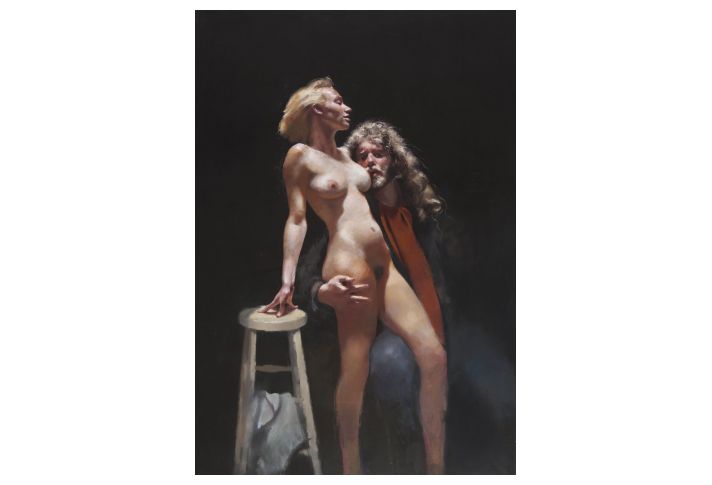

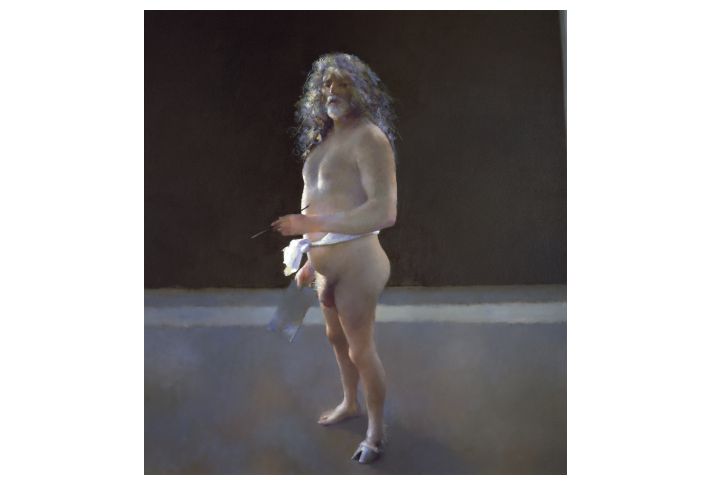

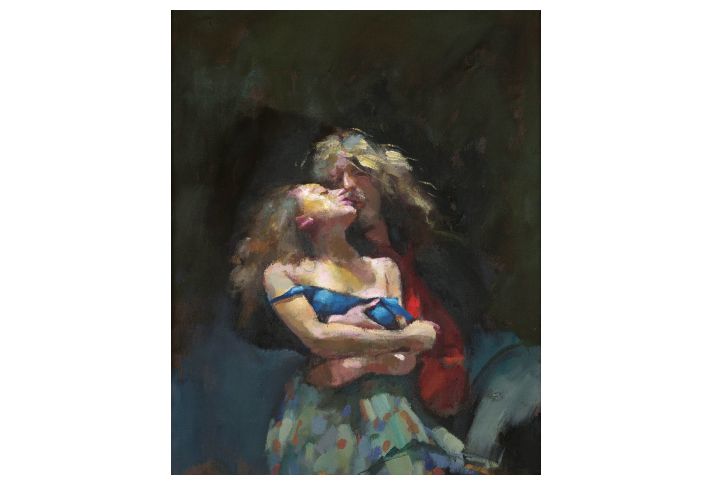

The acclaimed father of Christian Monasticism was St. Antony the Anchorite or St. Antony of Egypt. His personal struggle and eventual triumph was an epic moral tale of heroic asceticism versus the weakness of the flesh. The traditional metaphor of Lust is ironically presented in these studies with the painter as St. Antony. It need hardly be emphasised that the painter does not share St. Antony’s motivation. He is however, interested in the thesis that there is no fool like an old fool.

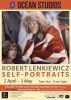

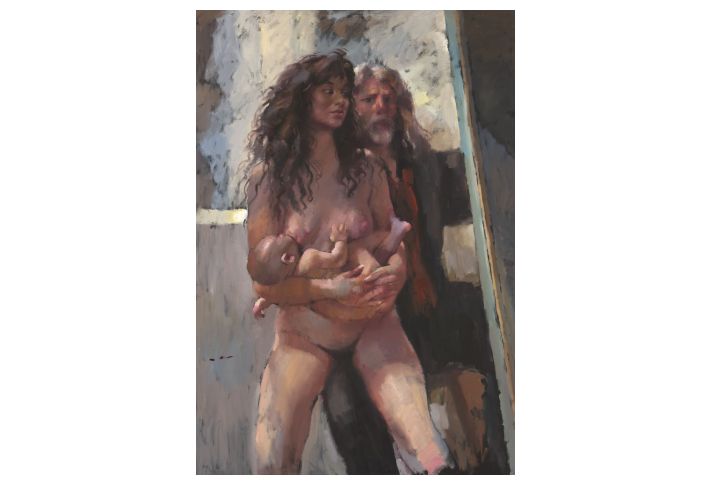

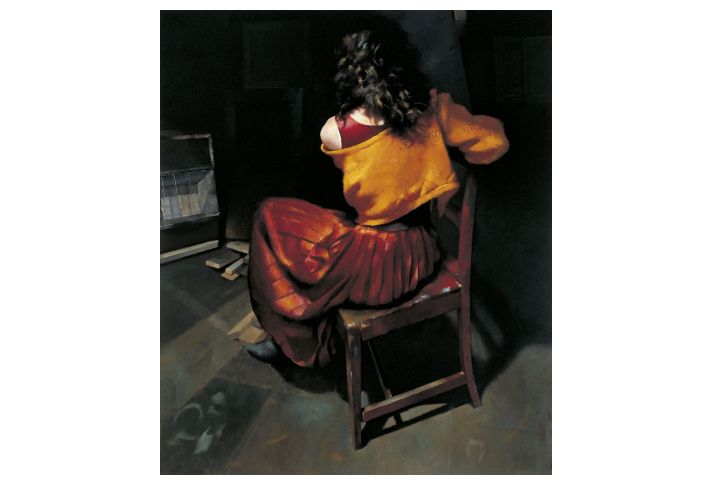

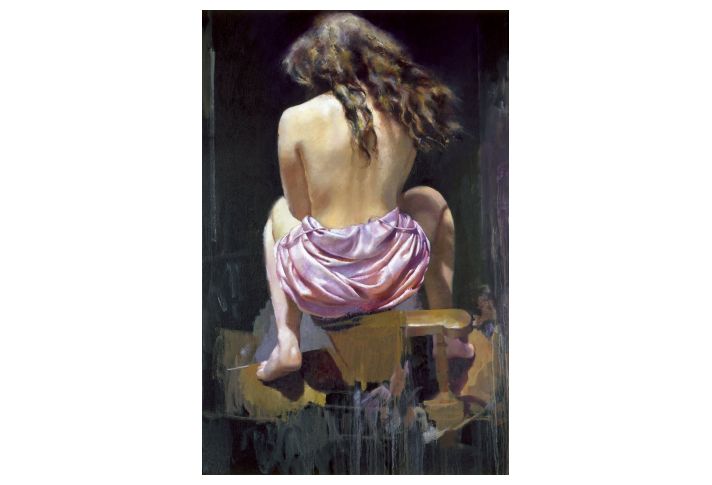

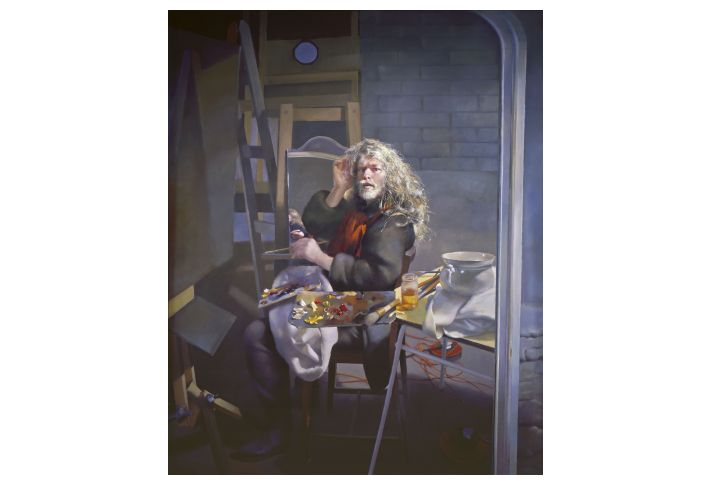

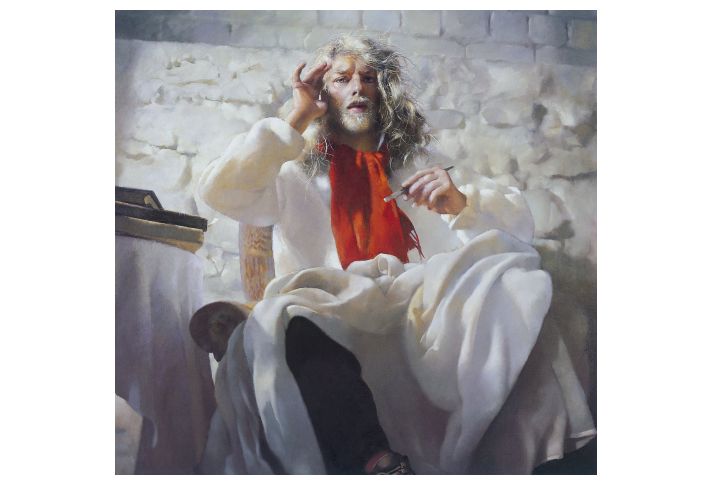

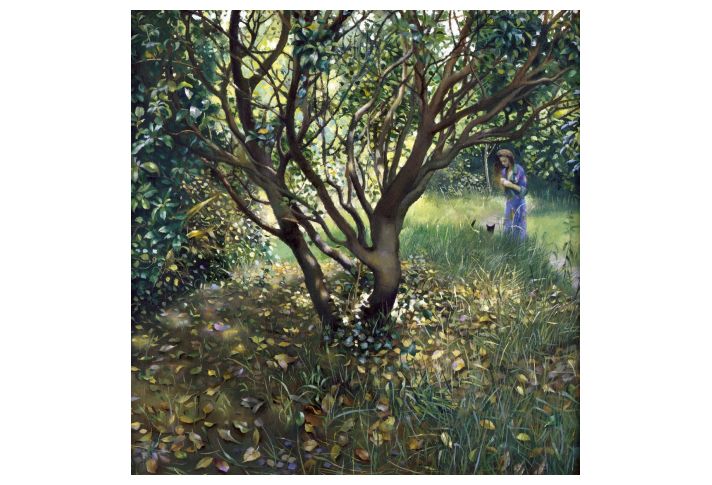

The thematic divisions were also marked by changes in painterly style. Early studies were loose and raw, generally with the model nude or semi-nude seated on the painter’s lap, who was usually garbed in a dark artist’s smock and a crimson scarf like the slavering tongue of a wolf. But Lenkiewicz wanted to capture something of the hallucinatory quality of St Antony’s visions with a heightened palette of oranges, saffron, purples and pinks. Everyday garments worn by his sitters, with their pastel high street hues, were replaced by a stock of visually and texturally saturated formal dresses or shawls.

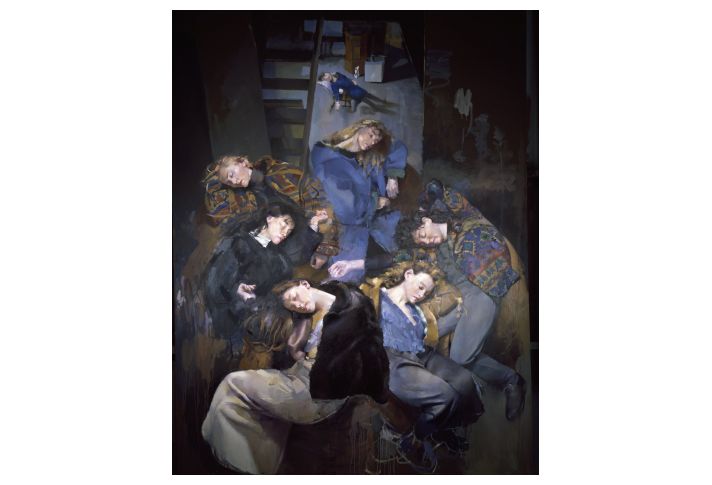

The centrepiece of the Project was a vast canvas 3.2m x 11m in size, The Temptation of St Antony. The canvas depicts a melée, fuelled by alcohol and lust, taking place in the street adjacent to the painter’s studio. Lenkiewicz would have witnessed the night-time revellers descending on the area, with its huge concentration of pubs and drinking dens, for over twenty-five years and had consistently fought against “brewery policy, which is to turn the world alcoholic to fill their pockets: they go for the young.”

The Project was also notable for generating large numbers of ‘relationship notebooks’ written and illustrated by sitters for the paintings with occasional contributions by Lenkiewicz himself, sometimes during or after the sittings. By agreement with their authors the notebooks would reside in Lenkiewicz’s library and

… testify to the general observation that the assumption of concern and regard for our partners has little to do with their welfare. Obsessional and addictive attitudes are cross-referential in our lives; art, men, women, children, ideologies, all are subject to purely aesthetic and physiological responses. The belief that we are concerned for the welfare of another person – independently of our own needs – is of a pathological character.

Unusually for the artist, Lenkiewicz chose to show the Project outside his own exhibition rooms. Sponsored by the Halcyon Gallery, The Painter with Women was shown at the Birmingham ICC in 1994. The hanging was carried out to Lenkiewicz’s instructions:

The intention was to try, without being kitschy in a Gothic way, to formulate a slightly dark, melancholy, cathedral-like atmosphere, with the paintings as the stained glass.

Seemingly concerned that the Project material would be misunderstood as “a catalogue of the painter’s love life”, Lenkiewicz persuaded his sponsors to add a retrospective section consisting of seventy-seven works from previous Projects. An essay by Dr Philip Stokes was quickly produced and published to supplement what Lenkiewicz viewed as the inadequacies of the official catalogue.

But understood or not, the ICC exhibition was a huge public and commercial success, and Lenkiewicz was able to carry his major passion – book collecting – to new heights. His antiquarian library on metaphysics, witchcraft and the occult, prime examples of the “fanatical belief systems” which so fascinated him, became one of the finest in private hands in Europe.