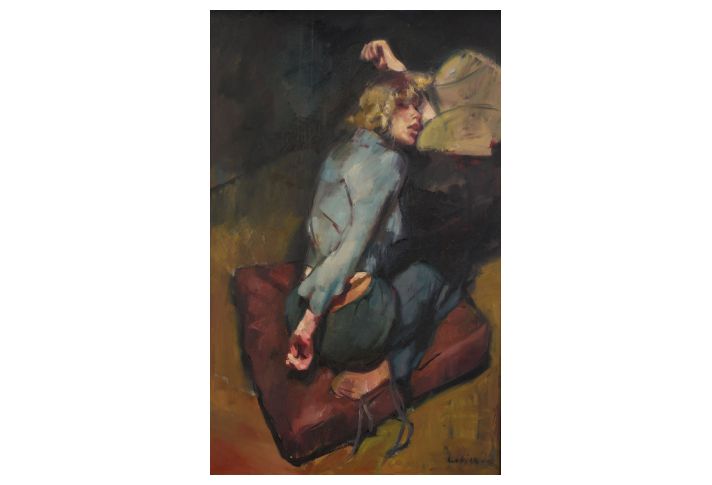

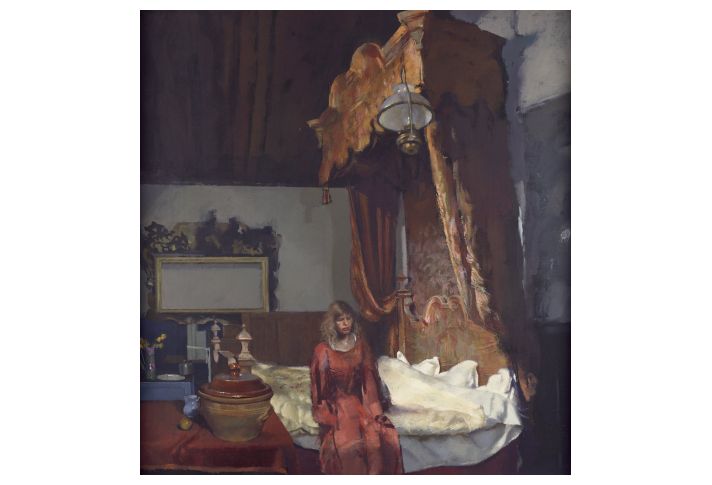

In an ‘aesthetic note’ dated 29 November 1978, Lenkiewicz records a tender scene between himself and Mary which occurred at 11p.m. in his studio.

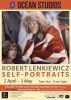

To ‘consciously’ prepare oneself for committed addiction. The peculiarities of such a venture. The pose above took two years to organise and stage. The reader might view it as commonplace. The reader might suspect that my companion was asleep; I must confess to similar suspicions on a number of occasions. We are both very much awake.

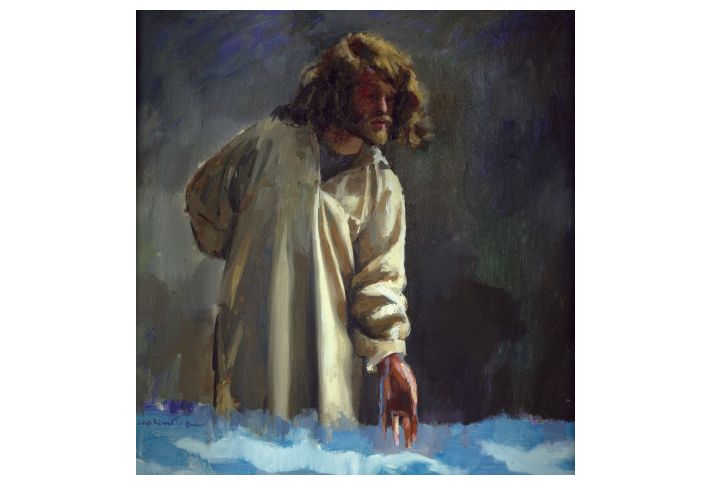

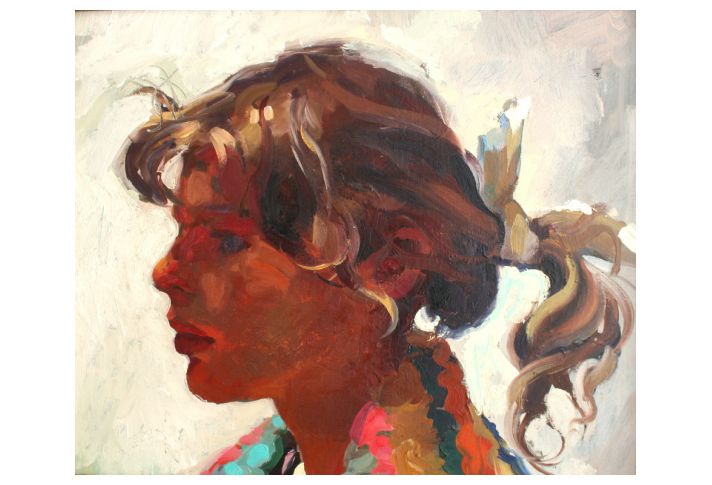

This note occurs approximately midway through the timespan of the large folio of collected notes and illustrations which has come to be known as The Mary Notebook. Every encounter with Mary, however mundane, is recorded together with the artist’s physiological responses to his growing dependency and obsession. The most intensive phase of notes are made on pale yellow sketchbook paper. “An unrequited passion is the lifeblood of creativity”, Lenkiewicz said, and in the notes we sense the dual passion – for the woman and the creative intoxication – as Lenkiewicz pours out his twin obsessions in a private language of “colour metaphors for physiological states”. By the time this note was created the character of the illustrations are changing. No longer must Lenkiewicz work solely from imagination and memory – Mary has returned to the studio a more willing model and the painter’s focus shifts to drawings, watercolours and easel paintings.

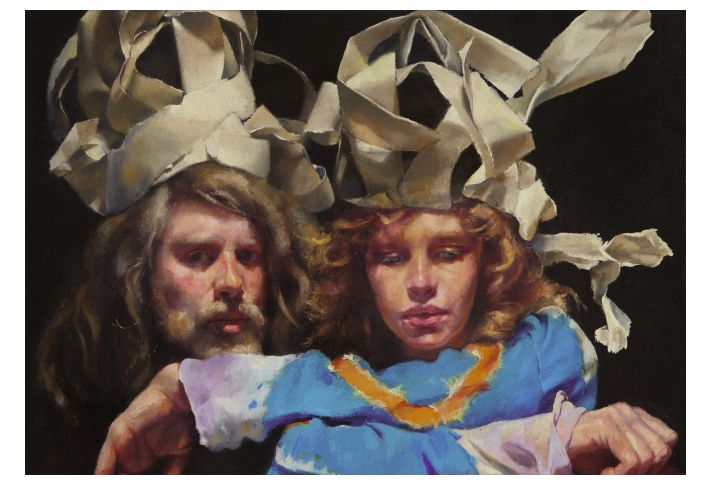

Mary, then eighteen years old, makes her first appearance in the painter’s diaries on 27 December 1976, four days before his thirty-fifth birthday. She drives him to the stately home of his friend and patron, Lord Eliot, where Robert installs Mary’s image high up on the vast Riddle Mural in the Round Room. As the artist later explained in the 1982 TV documentary The Leaves Were Full of Children (click here to purchase DVD), she represents “the prime articulation of Heaven, as far as mortal man is concerned, Woman, in the form, in this case, of the Virgin Mary” – Lenkiewicz’s private joke about his companion’s lack of experience. “She is afraid and, of course, she is entitled to her fears. What she calls ‘experience’ and what I call ‘innocence’. Oy gevalt!” he notes in his diary a few days later. “She agreed that authority in the situation was limited. I explained that the irreligious authority of her appearance was all she needed. Far more authority than I would ever have.”

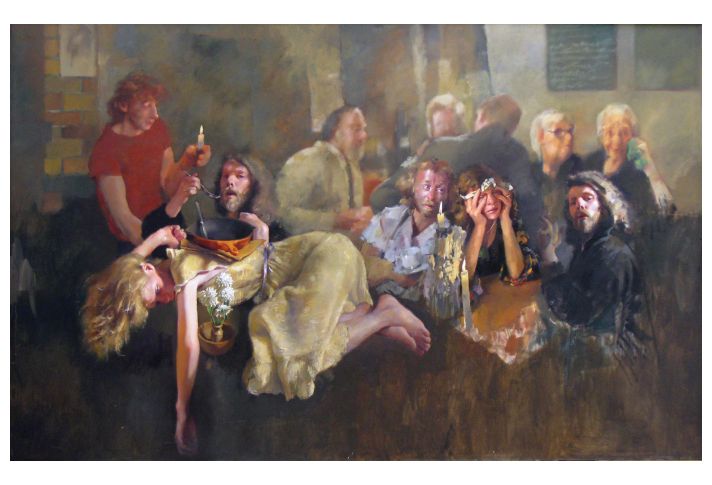

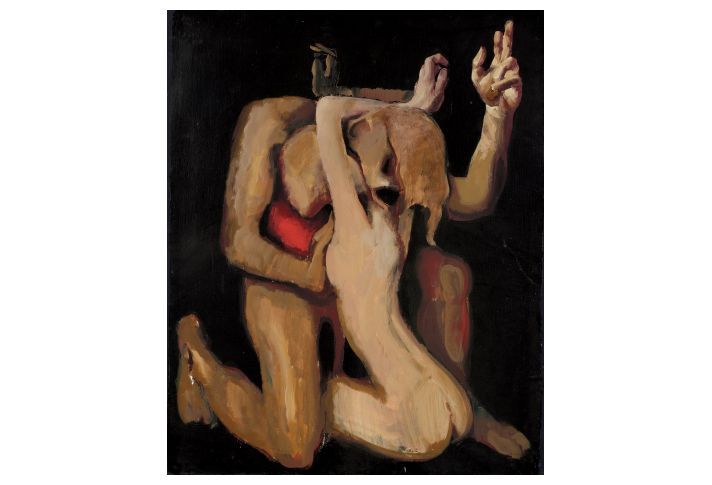

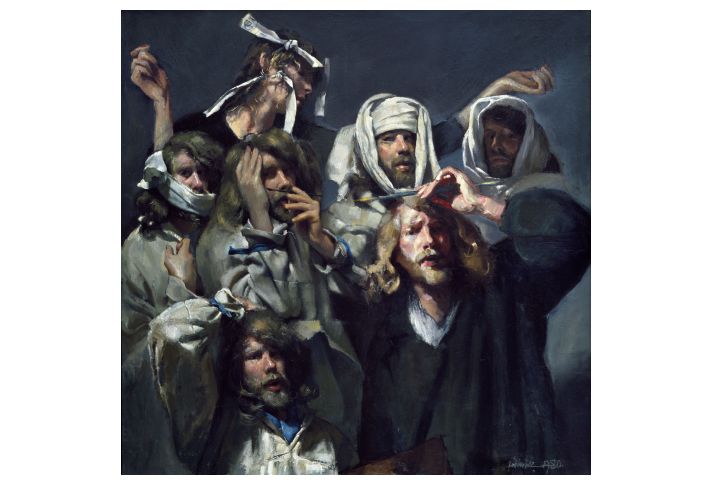

Mary is not unaware of the painter’s reputation for ‘experience’. The list of names at the end of the 1976 diary of women with whom Lenkiewicz has maintained concurrent sexual relationships in that year has more names than Mary has years. She is also disturbed by his thesis that a constant awareness of death is the greatest spur to a full life. The first date at Lord Eliot’s home ends with, “She is terrified of graveyards, so at midnight I took her to Ford Park Cemetery and philosophized – will see her soon.” She agrees to sit for a double-portrait in the jealousy theme but, disturbed by the atmosphere in the studio, limits the encounter to three sittings. Lenkiewicz notes on 2 February 1977 a “beauty and the beast state of affairs” colouring their meetings. It inspires the tondo Man Holding a Woman’s Dress Watching Her Walk Away with its brutish male figure.

Then Mary disappears from Lenkiewicz’s life for four months, one of the many endings, followed by new beginnings, which will ensue. She is absent from his life when Lenkiewicz’s mother dies in March. On 30 June 1977 Lenkiewicz makes this emphatic entry in his diary as she briefly reappears:

On this day I decided to take the earliest opportunity to commence a series of notes and observations on the parallel interactions between aesthetic experiences and the structure of one body. Such notes are prey to a ridiculous subjectivity, but the abortive attempt at a similar project two years ago may leave me less vulnerable to over-speedy assumptions and connections. Mary is perfect material for judging in detail the effects of one variation…

For anyone familiar with The Mary Notebook, which records the extraordinary course of this relationship up until the couple’s honeymoon in Rome in 1981, the idea that anyone other than Mary could have been its subject is startling. But Lenkiewicz would always maintain that his observations could only ever be about his own aesthetic response, not the ‘other person’. The aesthetic note dated 31 March 1978 (Orgasm Project) :

It is an exciting realisation to sense that ‘empathy’ towards the ‘other person’ is evoked by aesthetic formulas and is in no way connected with ‘moral’/’caring’ notions. Our ‘feeling for the other person’ can only be the refraction of one’s own aesthetic – the ‘other person’ never comes to exist throughout the relationship. Psychosis develops as a result of brutishly assuming vaporous feelings about the ‘other person’ – that render one insensitive to oneself and consequently the ‘other’.

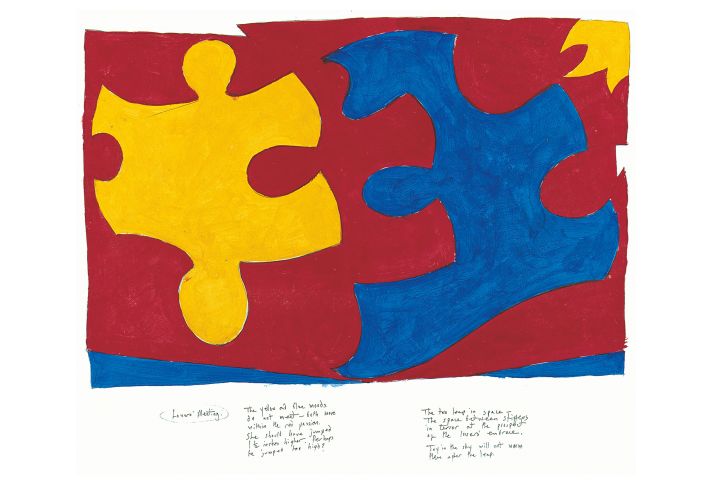

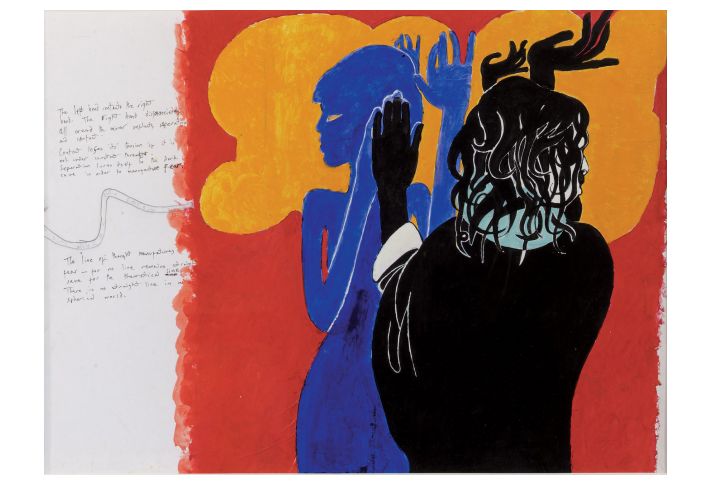

The folio and a number of aesthetic notes relating to Mary which had been framed as separate works (such as Lovers' Meeting [exhibited as Mary and The Painter. Red, blue and yellow], The Claw Moves in the Stomach, The Line of Thought Manufactures Fear and First Contact) were published as a facsimile called The Mary Notebook in 1998.