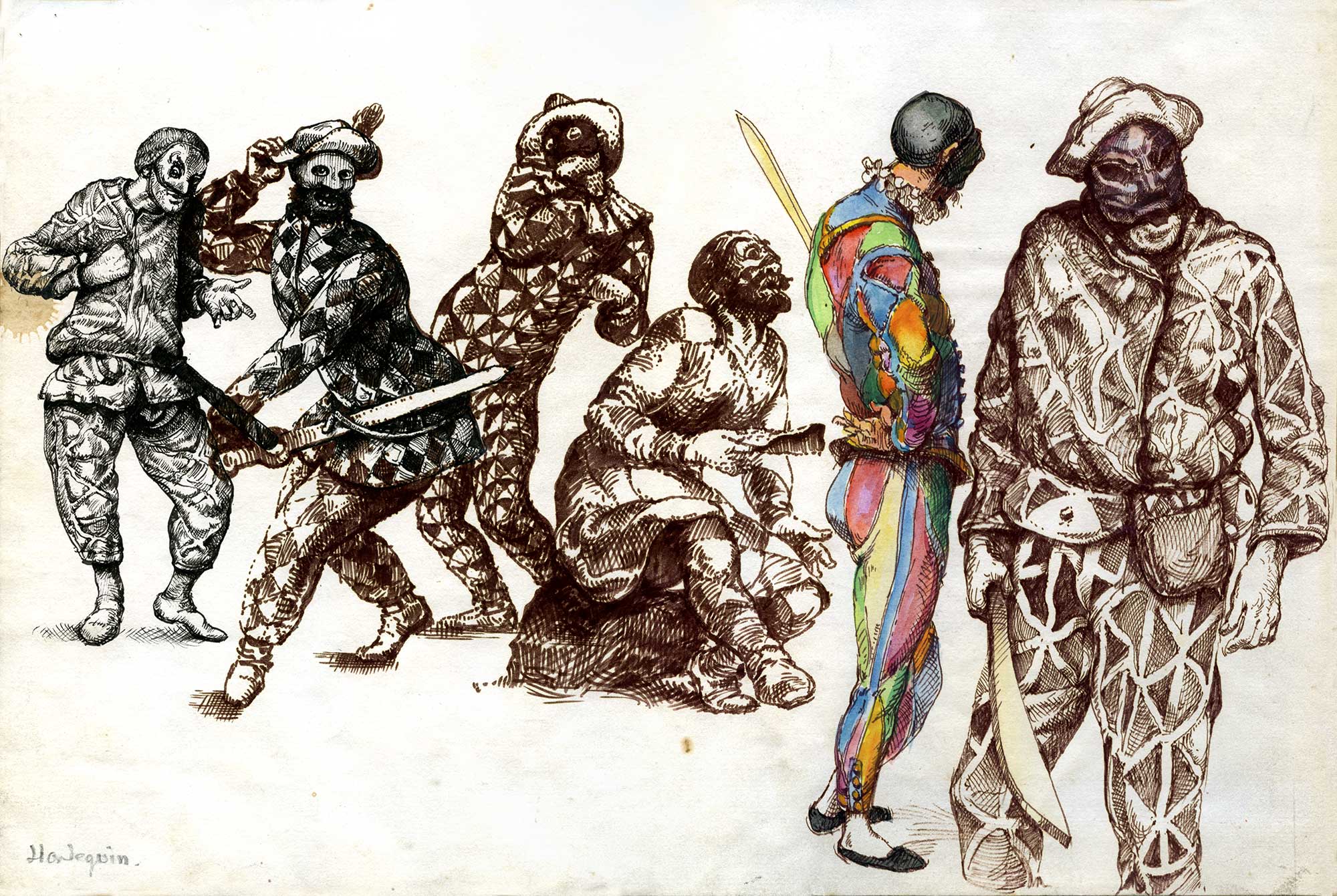

The History of the Harlequinade is a collection of notes and illustrations compiled by Robert Lenkiewicz c.1970 in relation to the theme of Commedia dell'Arte. The hand-made 18-page booklet is approximately A3 in size (see below for illustration sizes).

The notes discuss the principal characters of the masked-theatre Harlequinade tradition: Columbine, Harlequin, Pierrot, Polichinelle and so on. The images are not original to Lenkiewicz but are hand-drawn versions from the texts cited in the footnotes. But Lenkiewicz has also added his own creation, Pnoob, the innocent romantic fool who features as the artist's alter ego in many illustrations dating from the 60s and 70s.

A number of works from this period, especially those related to the Vagrancy Project, show sitters in Pierrot costume, or other garb from the Commedia -- ironic commentary on the nature of relationships. But the most extensive use of this imagery appeared in a large mural situated in the New Hoe Summer Theatre, which was demolished in 1982. Parts of the mural, which had been papered over in the mid-70s, were saved, including a self-portrait. A portion of the image which quotes a still from Marcel Carné’s 1945 film Les Enfants du Paradis (seen to the right in contemporary newspaper photograph) was also rescued.

|

COLUMBINE

“Old men are like trees. When they can bear no more fruit, they're cut down for firewood.” 1

The popular view of Columbine is that of the serving-girl with 'higher aspirations'. She has charm, wit, a sharp tongue, she is able to get out of many a difficult situation.

For centuries she has been the tractable participant of masculine expectations. She gave pleasure in male terms, she was permitted courtship, she was there to inspire romantic sentiments, and to witness man's self-glorification.

Women were not allowed to respond spontaneously to men or events, and when this was condoned it was only within the area that was likely to cast a suitable reflection on the 'lover' or some such person. In 1558 Pope Sixtus V issued a new edict forbidding women to appear on the stage; improvising - common on the commedia's platform - was not considered legitimate theatre, and consequently Columbine escaped the strict censure she otherwise risked.

All this contributed towards her domination, but brief familiarity with her views soon makes it clear that she had her own way of dealing with this problem.

As a member of the 'servette' or 'maid-servants' sector of society, she was in the position of witnessing the absurdities and foibles of her employers. Being the servant and therefore the confidant, she soon displayed a remarkable astuteness when proffering advice to less experienced and more hopeful mistresses

On the subject of coquetry, Columbine thus admonishes and advises her mistress Isabella:

"Things must never be allowed to go to extremes. But I assure you that a little pinch of coquetry scattered through the manners of a woman, renders her a hundred times more lovable and desirable. I but repeat the words of my mother, who was a marvellously well-informed woman on this subject. I have heard her say a hundred times that it is with coquetry as it is with vinegar: when too much is put into the sauce it becomes sharp and detestable; when it contains too little it is so faint as not to be tasted; but when you achieve that mediocrity which arouses appetite, it will induce you to eat your very fingers. It is the same with woman. When she is coquettish at the expense of her honour, fie, fie! that is not worth a devil. When she is not coquettish at all, that is still worse; her virtue seems confounded with her temperament, and you would suppose her merely a lethargic beauty. But when a beautiful woman has just so much sparkle as is required to please, faith, if I were a man, that should tell with me." 2

Columbine has learned of the value of fidelity, that it is worth very little as far as she can see. She has become something of a scholar, and is often to be found studying in the library of the Doctor, another notable and ill-famed member of the commedia de'll arte. The Doctore placed his learning at Columbine's disposal in order that he might then seduce her, but it is she instead who seduced him. His own folly is cruelly shaken in his face, nature has favoured him badly, and all the learning in the world will not compensate for that. Columbine's scholarship reflects her curiosity about life, the Doctor's is merely a manifestation of isolation and inadequacy. Columbine punished the Doctor many times for his impudence in assuming too much from their relationship. She is in no doubt about the manner in which the weaker sex is to be handled when remonstrating her mistress about invalid techniques in acquiring a rich and 'suitable' husband:

COLUMBINE. "You go about it in a fine way! Virtue of my life! When marriage is the aim more artifice is necessary. I have told you a hundred times tq assume a severe and haughty air with those who seek you in marriage. Man is an animal that desires to be mastered. He attaches himself only to those who repulse him. From the moment that you seem gentle and complacent any fatuous suitor may suppose your heart to be garrotted by his charms. But when you treat him with indifference, you will see him supple, arduous, attentive, sparing no pains or expense to succeed in pleasing you."

ISABELLA. "It seems, then, that I am still a novice, for I had thought that sincerity sustained by honesty must most surely win affection."

COLUMBINE. “Whence are you with your honesty? Go on singing that tune and you'll die an old maid. Get it into your head, mademoiselle, that with the man of to-day it is necessary to be astute alert, and roguish even. The great thing is to become a wife; the rest is in the hands of God." 3

Columbine seems to have loved both Harlequin and Pierrot; Harlequin, because it gave her the opportunity of mothering and being responsible for someone who could not be responsible for himself. Where Harlequin needed her, she was there, he permitted her to be independent but simultaneously appealed to her need to be needed. But Pierrot with his obsessive love for her, his romantic preoccupation with her welfare this was less easy for Columbine to take. It interfered with her independence, whenever she met him, she was very conscious of his vulnerability, of how anything she would say or do would make him lurch in tears. This interference with her natural life-style was something that she could not help resenting, but she knew also that his consistency, the infallibility of his infatuation was something she secretly depended on, and would always try to test, in order to determine its reality.

Columbine may be viewed - at one moment - as the archetypal flirt, at another moment she is less vacillatory, more determined to assert her own identity, not only as Columbine feat as woman.

It is this tendency towards self-assertion that makes her so attractive to the members of the Commedia as well as to her audience.

But is a self-assertion that is tolerated by an audience that finds her sexually attractive, try as she might she will not be able to evade the role she must play in a world whose demands operate through biological necessity.

Columbine (alias Bettia) is discovered in the arms of a lover, Tonin Ruzzante, her husband begs her to return, saying as he speaks through the window, that he will 'forgive her fault.' Columbine has the alertness to see it less as a 'fault' but rather his own inability to adapt to the facts of life; we leave her with the last words:

"I care nothing about your forgiveness; I do not need it. At home it is I who have to labour and I am sick of it. Whilst you are glued to a chair and never do anything I must set my hands to everything. Go and seek another servant to clean your pots and pans, and to do your house-work. Do you think that I, who am as fresh and lively as a fish, shall submit to having no society but yours?

I am here, and here I remain.

I am sorry about your honour; but you have brought this upon yourself." 4

1 See: The World of Harlequin; A. Nicoll. p.96.

2 See: The History of the Harlequinade; M. Sand, Vol.I.p.166. Also: Pierrot; K. Dick. p.123.

3 See: The History of the Harlequinade; M. Sand, Vol.I.p.68-9.

4 See: Ditto: p.161. see also: Pierrot; K. Dick. p.121.

|

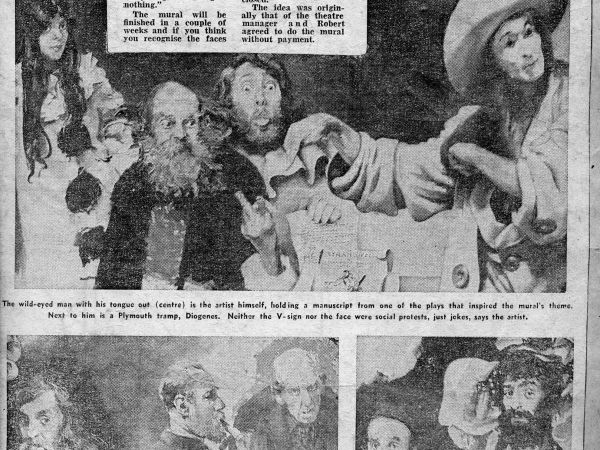

HARLEQUIN

‘Harlequin pretends to be a poor soldier and begs for alms. Cinthio approaches; Harlequin raises his cap: 'Sir', he says, 'Please help a poor dumb man.' Cinthio smiles: 'You are dumb then, my friend?' 'Oh yes, sir', replies Harlequin innocently, and on Cinthio's asking him how he can be dumb when he is able to talk, he eagerly gives his explanation: 'But sir, if I were not to reply to you that would be rude; I am well brought up, I know how one should act.' In the very moment of saying this, however, he suddenly appreciates his error and quickly adds 'But you are right, sir; I made a mistake - I meant to say I am deaf.' 'Deaf!' cries Cinthio, 'That can't be,' 'Oh yes, I assure you, sir,' Harlequin answers, 'I cannot hear even a cannon going off.' 'But at any rate,' says Cinthio, 'you understand what is being said to you, especially if somebody calls you to give you some money.' 'Most certainly, sir', is Harlequin's quick reply, and he goes on to claim that once more he had made a slight mistake; he really should have said he was blind.' 1

A cry and a sudden leap, a flash of variegated colour- yellow, red, blue -triangles contorting in rich lamp-light; disorganised patchwork catching light from torches, camp-fires and the moon.

Witty, but servile, paradoxically clever but foolish and vulnerable; and always the mask of a negro.

The significance of this mask will be returned to later, and it is one that reflects an aspect of Harlequin that makes him perhaps the strangest and most intriguing of the group.

Harlequin is a cheat, a liar, he procures for others, and tries to reap the benefits himself. He is athletic and agile, but frightened of violence. The man who does not really wish to hurt anyone, but who would not really care if he does. He attracts situations by deceiving himself and others; amusing colourful and at times clever, he is able to adapt himself to the moments opportunity when exploitation is at hand.

From the 18th century onwards he becomes known in one context alone. He is the romantic lover par excellence, a dancer, insolent, and gay, a passionate gallant able to play all the fashionable games, and to create a sense of intensity and import in all and every trivial escapade.

It has been observed however, that his response to woman may not have been quite as virile and positive as popularly imagined.

Instinctively, he felt that all woman were whores, if not now, then later. If not with him, then with someone else; what after all, was the difference. Their availability was in no way connected with him, but rather, with their own inherent weakness and willingness to hand themselves to almost anyone.

If he refused, well, what of it? he had only to look a little taller, a little darker, change his stance, quote a certain poem, and everything would go well. He knew this to be true, so it was unnecessary to take the trouble. No wife was faithful, it all depended on the circumstances. Fidelity was absurd, all women were alone,; it was just a matter of timing. They need not frighten him, because he knew that it was they who were afraid, not of him, but of life, of change. And that was all that Harlequin needed, that knowledge made it all so easy.

He was, in short, fundamentally contemptuous of women, in much the same way as he probably was of men.

His 'innocence' for that is what he in part believed, relinquished him of all responsibility. His 'love' for them was unreal, a tricky thing, so likewise their affections for him were of the same stuff. They seemed unhappy? Even miserable? So, what matter? He didn't believe it, and if they wished to be unhappy for months even years, well let them; it helps them to pass the time. 'You should not tempt a simple lad whose standard of honour is that of a child's' he would say; and the woman that pined for him would soon be pining for someone else. It was human after all, quite a normal thing, hardly a serious matter.

Traditionally Harlequin's role was to court and marry Columbine, and their history of mutual affection, with the silent Pierrot in the background is well known to many. But so many times they are faithless to each other, so many times they become quite independent. He and she, the archetypal flirts, who are drawn together, because they are reflecting the same truth; their vulnerability to events, to whims and fancies, they console each other with the recurring knowledge of all things fading away.

A further suggestion, and one with fascinating possibilities, is that his basic contempt for women, was that he deceived himself about his own nature. Time and again the scenarios display his interest in women's clothes, in fashion, and feminine things,. Life and his profession forced him to womanize, it was expected, but really he was only 'interested' in them. His ease and affinity with women, was due more to their similarities than their differences. They were able to confide in him, they loved to listen to his advice on matters of love, and he was able to provide solace and opinions indefinitely, because, somehow there was nothing to lose. He dresses in women’s clothes, advises Columbine on every detail of make-up and fashion, and in a Dutch scenario of the I8th century is even depicted as being the 'mother' of a child.

The popular conception of a Prince Charming Harlequin is uncertain, because harlequin is the result of his own 'publicity campaign'.

"Yet this ambiguity is the key to Harlequin's character. He could never really be himself because he was never quite certain what that self was. He was able to be emphatic about the variety of the selves he played, that is in the conventional sense, because he was real in his unreality: indeed he exaggerated each self because there was no 'real self' in Harlequin". 2

The undertone of homosexuality in Harlequin's character may be seen as symbolic of his being 'neither this-nor that'. He has spent centuries behaving superficially, avoiding all personal assessment. At every turn he backs away from what the world calls reality, until his own identity became so fluid that it adapted itself to every whim and fancy.

In a sense, we are all harlequins. In deceiving ourselves we deceive others, and it is this pattern that gave Harlequin an unreal quality.

This quality may be likened to what we all feel at times, that we do not really exist at all, except as whimsical paper-tigers in 'other people's' fantasies.

Apart from Harlequin's servility already alluded to, the slaves or negro's mask that he wears helps also to indicate the darker or sinister side of his nature, that side that cannot be relied upon, that may go willy-nilly according to unknown dictates. One very interesting observation about harlequin which may be entered here is the amazing contrast between his image as we now respond to it, and that image from which he was born in antiquity. Today he flits about a stage in Peter Pan fashion, a century or two ago, he had more panache, more daring, though he was still weak and vulnerable to every incident. But earlier still, in the middle ages a number of individuals wearing patchwork garments appear to have wandered about communicating by signs and cryptic words.

"This strange figure is known to have operated in Spain and elsewhere in Europe. The name given the silent teacher who performed strange movements, incidentally, was 'aghlaq' (plural 'aghlaqin', pronounced with guttural "r" and European "q" as 'arlakeen','arlequin'). This is an Arabic play upon the words for "great door" and "confused speech." There can be little doubt that his appearance to the uninitiated is perpetuated in the Harlequin." 3

Harlequin's earlier ancestors may have come from a company of Greek comedians, he may indeed be of African extraction, he may be an isolated European invention, but always he danced, jumped around, became talked of as that fellow who was 'always in the air'. We may leave Harlequin with the last word:

"I was very naive, not to say stupid, my masters; but with age, experience and wit came to my assistance, and today I have all that I need and some to spare." 4

1 See: The World of Harlequin; A. Nicoll. 1963. p.72.

2 See; Pierrot; K.Dick.1960.p.109.

3 See p.352; The Sufis, I. Shah. 1964.

4 See p. 57; The History of the Harlequinade, M. Sand. 1915.

|

POLICHINELLE

“You'll all end in dust!"

Of all the members of the commedia de'll arte none is more terrifying and more serious than Polichinelle. We may take the braggings, illusions, and melancholies of all the 'family' with a pinch of salt; we may smile knowingly at a remark here and an action there, but it is all permissible, all half-truth.

But Polichinelle; with Polichinelle we may not smile, unless in smiling we are prepared to lose our very life.

Polichinelle is dangerous, he was the only man that Columbine truly feared, he came from a force, or a condition that she could not understand; Polichinelle had about him the feel of the satanic.

We are to imagine that he has just strutted across the stage, large, thumping, he carries a great stick, a brutal looking cudgel; an enormous black nose, red cheeks, and two massive humps behind and to the fore. Swaggering in cockerel motion he screams out the raucous hen-cry:

"B-R-R-R-R-R- B-R-R-R-R-R.... Yes, my children! Here I am! I, Polichinelle, with my big stick!

Here I am! The little man is still alive you see. I come to amuse you, as pleasantly as I can,, for certain people have told me that you are sad!

Now, why should you be sad? Is not life a pleasant thing, an idle jest, a veritable farce, in which all the world is the theatre and where there is plenty to excite your laughter, if you will but take the trouble to look?

It is getting on for 4,000 years, my children, that I have been parading my humps about the surface of the globe, among men who are no whit less ferocious and savage than tigers and crocodiles; and it is getting on for 4,000 years that I have been laughing, until I have had a pain in my back.

Is it not droll, is it not very droll, tell me, to see upon such a little space as that which we call the world, this ant-heap of creatures, each of which, taken separately, conceives itself to be privileged by all nature?

Ask one of these atoms if it would change its skin with its neighbour. Ah, no, be easy, its own skin pleases it too well. But ask if it would change its purse with that of its neighbour. 'Oh yes, if his is bigger than mine', it will answer you. And each one strives, comes, goes, amasses, stirs up, rolls, grovels, and gives more thought to tomorrow than to yesterday. You would suppose to look at them that they must live for ever.

They are all mad!

.... That is the law; to make and to unmake. Behold me this fellow, who plagues his brains to discover some means of attracting the attention of some other unfortunates who do not wish to be turned aside from the road which they follow, which their fathers followed, and which their children will follow. He has had some sort of a notion to disturb his neighbours; they seize him, shut him up, or have him burnt or drowned. Is it not droll? Ah I You would have laughed to have seen thousands of human carcasses hanging from the trees by the roadside after I know not what jests had gone through the minds of some lunatics. I never laughed so much as some fifteen centuries ago. There were whole roastings of people whose tort it was to be weaker than those who were stronger at the time. It was very amusing to see them rent and devoured by wild animals. Ah! You're going to call me a dull fellow, a fool, and to tell me that I have not understood what I have seen. Pish! My children! It is best to laugh at things, for the children of these disembowelled wretches avenged themselves later on.

After this splendid self-introduction, we are quick to realise that he is the eternal policeman, the authority figure in any social unit. He may be relied upon in any position of power, because he will not be swayed by petty considerations. Morality - of any kind -5 such concepts as guilt, conscience, are for him pathetic compromises with nature's wild force, even evil dynamic. Nature cannot be compromised with, Polichinelle's nihilism combat that of Nature's, and to maintain that combat was the only sense in life. One is not to be tempted to see in this something heroic, on the contrary, Polichinelle is not moved by heroes.

He had his weaknesses, woman and drink, on which he endlessly spent his money and constantly incurred debt. He was confident of his ability to seduce woman:

"I have no illusions about my physical attractions, but I have secret ways of charming the fair sex who are complex and strange in their whimsical infatuations. Women I like most after I have drunk my fill and beaten up a few nobodies."

The psychologist might argue that nature had left him deformed and so he avenged himself upon a world that would not accept him so readily. But it is not so simple, Polichinelle has appeared all over the planet at various times, and occasionally in a very 'good-looking' guise.

Polichinelle represents the man who will not and cannot accept faith as a suitable alternative to ignorance, rather like the Wandering Jew, he must re-appear at all times to wreak his vengeance upon the 'small men' of the world; upon the idolaters, the artisans, the creative one's, the believers, in short - the deluded.

"But droller still, the drollest thing of all, is woman. Ah! Now there we have a strange animal! Oh, the vanity, the malice of these little beings, for whom I am still capable of committing follies! By Satan! It is good to watch men and women desiring each other, deceiving each other, hating each other. The two sexes have declared war, and yet neither can live without the other. Ask a man what he thinks of a woman. He will reply: 'They are vain and untruthful.' Ask a woman what she thinks of men. She will say: 'They are egotistical and perfidious.' Come, come! There is truth on both sides, because with gold either may be bought! Be rich and you shall be honoured, loved and flattered; you shall be beautiful, even young if you please; you shall find love, consideration and honours. Be poor and you shall not be worth a string of onions!”

He was able to control by force, the curbing of 'revolutions' was his ideal trade. He had the intelligence to justify all and any of his brutalities by the use and exploitation of the 'law'. He was ready and able to ensure submission from his listener it was a pre-requisite for the recipient of Polichinelle's 'wisdom' to be thankful for the 'enlightenment’.

"I can see from here one or two who do not share my opinion. They may please themselves; they are still young. If, like me, they had seen whole cities disappear under volcanic ashes, if their shoes had been scorched by the hot lava of Vesuvius, ... if they had told the proudest nations of the world that they were no better than savages and brutes, they would think differently, and they would consider the matter carefully, before contradicting me.”

His 'big stick' was the law, and there was an end to the matter, This stick could take on may disguises, and at times it would seem as though he had been momentarily divested of his thugishness, by some 'good' force; but it was an illusion that would last only a moment, before Polichinelle would leap joyfully from the new 'good' to demonstrate again how adept he was at disguises.

"Is my conscience wide and easy? Of course it is! That which belongs to others belongs to me; and I have only to stoop so as to fill my hat with the gold and the wealth of my neighbours. You find that wrong? It is my point of view; I have such a contempt for men that I am little concerned with what they may think or say of me."

It appears that Rome fathered Polichinelle's parents in the form of two buffoons called Macus and Bucco, the one shrewd, intelligent, and aggressive, the other a braggart and a thief. From Macus he inherited his long thin legs, his humped back, hooked nose and protuberant stomach, from Bucco, his reputation for the cutting phrase and the cruel tongue. The identification with the chicken comes also from this period, Polichinelle's strutting has been likened to the hen-step, or, more recently, the goose-step. He could mock and taunt like no other of the Harlequinade, and his grotesque manner must have been almost hypnotic. It is not difficult to find equivalents in history.

"Take care! I have never been insulted with impunity, and I am never more to be feared than when I am laughing. You do not deserve that I should waste my merry words upon you, because that which should make you laugh, seems instead, to annoy you. What! Would you weep because everything goes wrong!

.... I am laughter incarnate, laughter triumphant!

So much the worse for those rows of paper capuchins which are to be overthrown by the first breath that blows.

I am of wood and iron, and as old as the world!"

In a scenario of a Neapolitan theatre Polichinelle (Pulcinella) has been captured as a murderous brigand-chief, he permits himself calmly to be led to the scaffold. When, however, the hangman is ready, Polichinelle plays various tricks with the rope feigning stupidity and pretending that he is unable to work out what it is for, or precisely where the noose is. 'You fool' shouts the impatient hangman, 'Look! It is thus that the noose is adjusted!' And the hangman slips his own head through it. Pulcinella seizes this favourable moment, takes hold of the rope, and strangles the hangman, crying to him: "How now!? Am I still a fool?"

In the middle of the 17th century Polichinelle seems to pass from the stage to the marionette theatre, where it is not long before he becomes known as Punch.

As Punch he was allegedly in need of twenty two virgins at a time in order to satisfy his sexual appetite. It is of no little interest that England should embrace this little character with his pathological undertones with such affection.

It would be appropriate to quote here the 19th century French authority, Charles Magin, and with his words we leave Polichinelle for a very short while.

" . . . Above all do not suggest that he is dead. Polichinelle never dies. Do you doubt it? You cannot know then, what Polichinelle is. He is the good sense of the people, he is the alert sally, he is laughter irrepressible. Yes, Polichinelle shall laugh and sing and whistle as long as there are vices, follies and eccentricities in the world. You see then that Polichinelle is very far from being dead. Polichinelle is immortal."

|

|

|

Newspaper cutting showing the original mural |

|

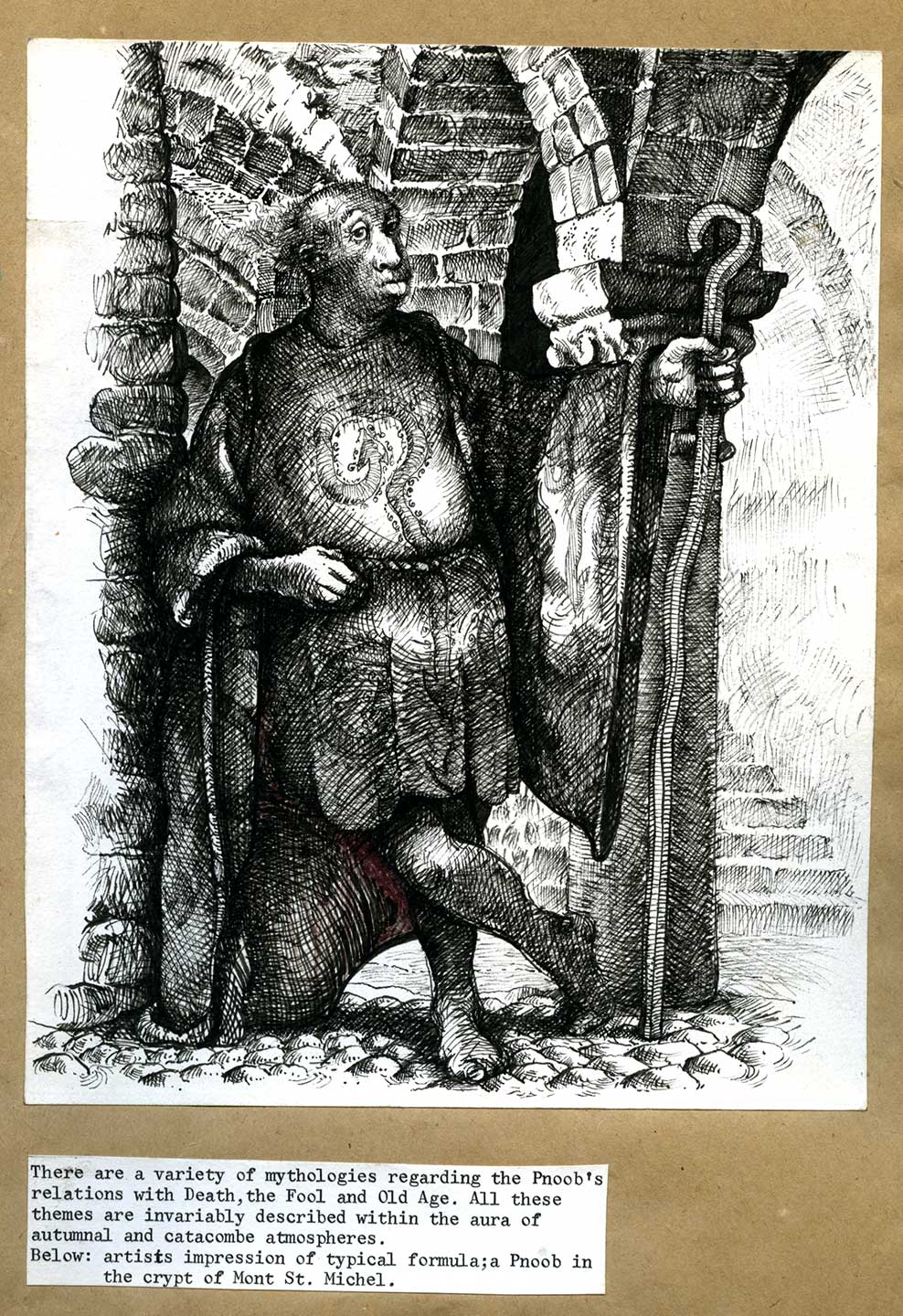

PNOOB

Scholarship has recently uncovered further details about a member of the Harlequinade 'family1 hitherto a mystery.

Pnooboniae, Pnoobis, Pnobus, or, more popularly the Pnoob, has remained virtually unrecorded in the characterisations, scenarios and illustrations of the Commedia dell Arte.

At 12 noon on April the 1st 1971, Professor Guardi of the Italian Academy in Naples was leafing through several manuscripts in an effort to gather further information about 17th century horticulture. On Folio 17 recto of MS, Cat,no.IIII, was found the following reference:

" ... and thereon We kept close to the passe/seeking herbes of manie kindes/Whilst bending lowe, our friende Mr Pecorini cried oute/Hey! Ho! What is this?/Whereupon all ranne to the spot of our friende, and did ,ask him to explaine himselfe/And he did poynt to a Gullie deepe in a clefte of erthe in which we espied a sight of much;curiosity. Our Astonishment was wedded with much mirth when a straunge figure came a-leepinge from the bowels of the erthe crying out with a fearfulle hoyse.

This man/yf man he was/ could not be solaced and would take rib kindnesse for his humourS sake. There was much and greate merry-making mongst us all, but twas playne to all that the cause of our delighte was deepe melanchollie. Our merrie-makinge was enhanced by his garbe and his bearinge/ and above all thys/the manner in wych he did disport himselfe/ wych cannot be described in wordes/Nay, but rather was somethyng to be seene to be believed.

Before we had answere to oure sundry questions/he was up and awaye over the hilles and dayles makinge much squackinge sounde as woulde a greytlye upset Cockerall. We did muse that he was one of a travellyng bande of minstrells come to enterteine in Napoli as is oftentimes the fashione in these troubles dayes./ But we wondered at hys manner for he dide communicate much to us in hys straunge waye/but yet communicatinge little or nothynge/and we did eache of us returne home with a sorrie bent of minde and a gentil heavie melancholie ..."

This early allusion to Pnoob is of double interest to us as it indicates how much a part of normal life the travelling commedians were. Regrettably, the physical description of the Pnoob left by the Italian botanist is meagre, but we are left in no doubt of the effect of their strange companion.

First there is amazement at his appearance, then a great deal of laughter and fun, and finally, an odd depression that they cannot explain. We may sense, that their experience has left them with a feeling of disatisfaction, they seem to have apprehended a certain essential futility in their lives.

This may be reading too much into an isolated remark from an elderly botanist, but we may be more willing to entertain the idea in the light of some further evidence.

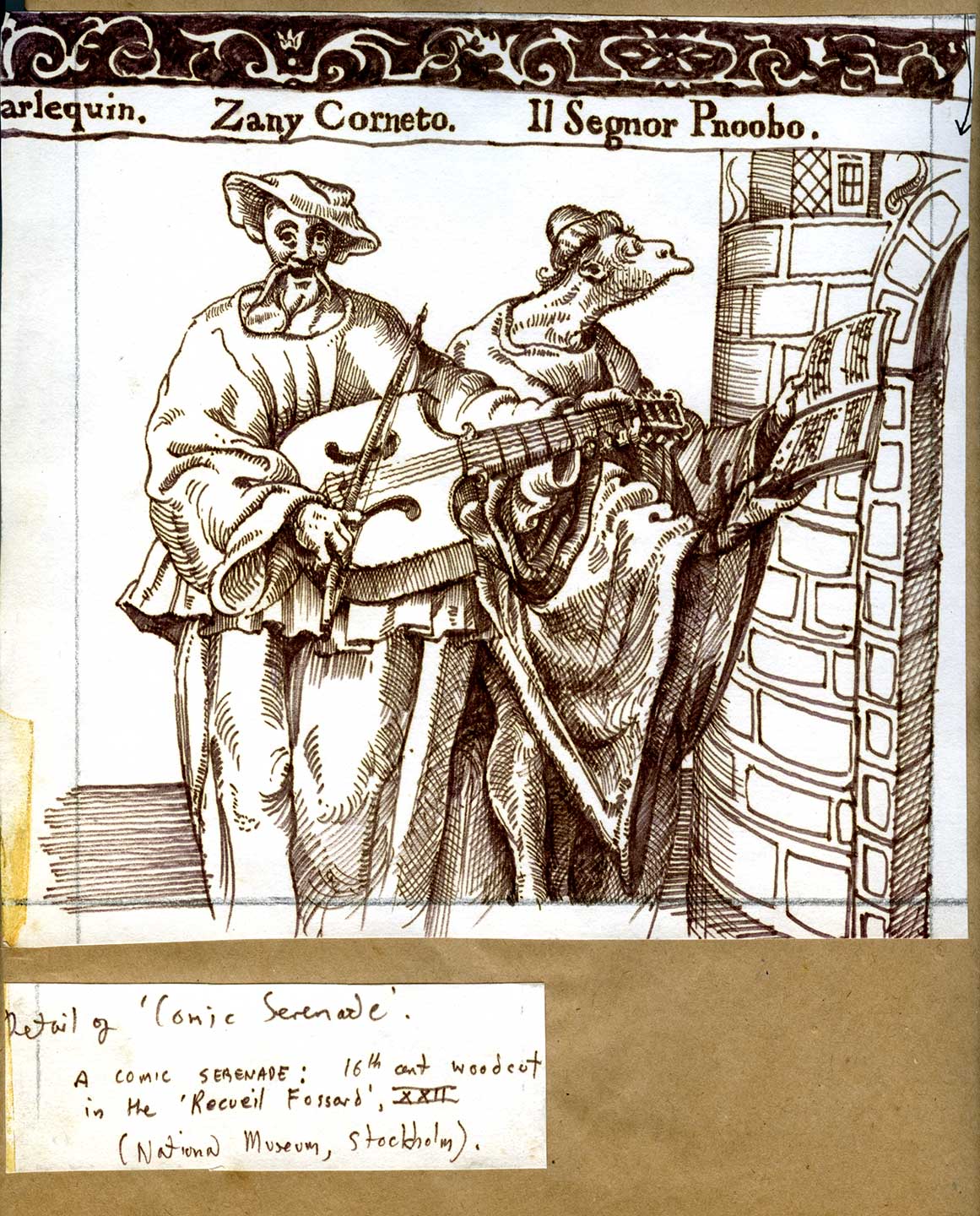

Illustrations of the Pnoob are rare, as far as is known only two such devices exist. One is now lost, and the other: (see illustration) is a woodcut of the 16th century to be found in a collection of illustrations depicting personae of the-Italian Theatre. The figure beneath the margin-heading 'Il Segnor Pnoobo', may be seen studiously engrossed in musical activity. He wears a long sage like gown gown is an indication of total nudity.

Though at first eclipsed by the Zany character with and a semi-oriental cap. Beneath his the instrument, we are soon made aware of a moving plaintiveness in the bearing of this Pnoob.

He is at once withdrawn and independent, ostentatious in apparel but discreet in manner.

We have here a priceless record of what must be one of the Commedia dell Arte of the most underestimated personalities.

The perfect mime, silence incarnate; the mysterious 'anonymous' with which all poetic collections commence, is here exemplified in 'Segnor Pnoob'.

Our empathy for Pnoob may be further observed through the famous verse of a late Italian scenario allegedly by the hand of Pnoob himself.

In 1717, a pot-pourri of anecdotes was published under the title of 'Quips and Pleasantries of the Arliquinadia'. At its conclusion is a detailed description of incidents at a local carnival where a theatrical company were entertaining.

The conclusion of these notes will find few items more suitable than Pnoob’s own symbolic'/ words and actions.

"... the whole group would clamour; ring bells and draw down upon itself the attention of the world. Banners of many colours, bells of many sounds, and great leapings and tumblings that one would think the whole platform to collapse from such calamity.

Of a sudden, silence would reign as becalmed sea in the dead of night. From the midst of the zanies would rise up the strange noise of a cockerel, and, following the noise as a donkey would a carrot, there emerged from the still throng the strangest of the company. Strange, for his manner, strange, for his noise, and strangest of all for his conspicuous absence until now. With a screech, he leaps to the forestage with thin naked legs and a great cloak.

Crowing all the while, he surveys the crowd, and, of a sudden speaks:

'The sight of a leaping Pnoob brings joy

The sight of a weeping Pnoob brings pain.

For he that leaps will be the toy

Of him that weeps and goes insane.

Leap not, oh leaper, for it is not yet the time

Tho’ you leap and weep you will never end this rhyme.'

Silence spreads heavy o'er audience and actors, and Pnoob does his great dance, leaping from foot to foot in clumsy stooped and crooked fashion he encircles acrobats and zanies alike, who, at the third round, join in with a might vocal roar and clangour.

Hysteria governs, like a flock of insane geese in a ring of fire they leap and jump till the platform might shake to bits. Chaos makes way for nothing; and suddenly, Pnoob is gone. Mayhap he is in amongst the actors, mayhap, amongst the audience; as I watch them now … I no longer know who is who."

PDF of booklet

http://www.robertlenkiewicz.org/sites/default/files/u2/lenkiewicz_historyoftheharlequinade.pdf

Image sizes (PAPER SIZE 335 x 480 mm)

COLUMBINE

250 x 250 mm

HARLEQUIN

285 x 422 mm

POLICHINELLE

280 x 420 mm

PANTALONE

266 x 360 mm

THE CAPTAIN

390 x 300 mm

PNOOB1

200 x 208 mm

PNOOB2

218 x 173 mm