The Old Age exhibition was staged to benefit a charity, but the commercial response was disappointing. However, the lesson of art history that an artist’s work is only truly valued after he is dead was not lost on Lenkiewicz. In 1981 Lenkiewicz would put that theory to the test in another show whose proceeds were intended for Age Concern, Still-Lives, but in circumstances in which the charity had to publicly disclaim being a beneficiary and Lenkiewicz would conclude: “My work is valueless – dead or alive.”

On 1 February 1981, Lenkiewicz had placed his own obituary in the The Times newspaper. "I could not know what it was like to be dead; only what it was like to be thought dead," he explained. Lenkiewicz had primed a number of associates, including his brother, John, to report that the painter’s health had indeed been deteriorating in the months prior to his sudden demise. Lenkiewicz meanwhile was ensconced very comfortably some miles from the city at Port Eliot, the stately home of his friend and patron the Earl of St Germans, at work on The Riddle Mural, a mural on canvas on the walls of the 12m diameter ‘Round Room’.

The original date planned for his ‘resurrection’ was 11 February but the hoax was soon rumbled because of the absence of a body. Lenkiewicz was obliged to return early to dampen the furore surrounding his stunt. Told of his brother’s miraculous return, John Lenkiewicz told The Western Morning News, "It seems that the preliminary diagnosis was unnecessarily sombre. We are all delighted he has recovered."

The resulting media frenzy and the tone of the local press’ letters pages suggested that this time the painter had gone too far. Whether in chagrin or in defiance, on the night before 1 April 1981 Lenkiewicz whitewashed over the vast Barbican Mural, which had first endeared him to ordinary Plymothians, and replaced it with an image of three flying ducks, that icon of English domestic bad taste. Two collection boxes were left on a trestle to enable the public to ‘vote’ on whether to restore the original. The outcome of the ballot was not recorded, but the whitewash was removed shortly afterwards.

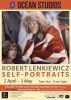

Amidst the furore surrounding the well-intentioned death hoax, the content of the brief Still-Lives exhibition and its pun on ‘still lives’ was overlooked. But in the window of the ‘dead’ artist’s studio was a painting which foreshadowed 1981’s main Project and was to become one of the artist’s most haunting images, popularly known as The Chairs.

The image of an empty chair as a metaphor for someone’s absence had been a recurring theme in Lenkiewicz’s work since student days. But here, the chairs signified the departure of Mary, the inspiration behind the only Project to bear a woman’s name – The Painter with Mary: a Study in Obsessional Behaviour. The “obsessional behaviour” in question was Lenkiewicz’s. In 1977, aged 36, the artist conceived a passion for this muse, then less than half his age, and decided to make “aesthetic notes” in which he would record the process of infatuation. Normally more interested in the decay of relationships, this would be his first serious exploration of “the ascent”.

But at the beginning of 1981, Mary had announced that she would be severing her ties with the artist. Lenkiewicz’s diary reveals that the painting of The Chairs, completed over seventeen traumatized days, is a record of his intense withdrawal symptoms. “Every painting is a self-portrait,” said Lenkiewicz and even if nothing else about the Still-Lives Project could be taken at face value, then at least The Chairs did genuinely record a kind of death agony.